“But what should our own verdict be on [her]? Does Elagabalus deserve to be more widely or favourably remembered today? One could perhaps single out as admirable [her] determination to be as open as possible about [her] sexuality and about [her] own perceptions of [her] gender. But what of [her] equal determination to enforce [her] own religion, or [her] habit of having [her] critics murdered, or [her] attempts to dispose of the young Alexander? . . . "

-John Edale

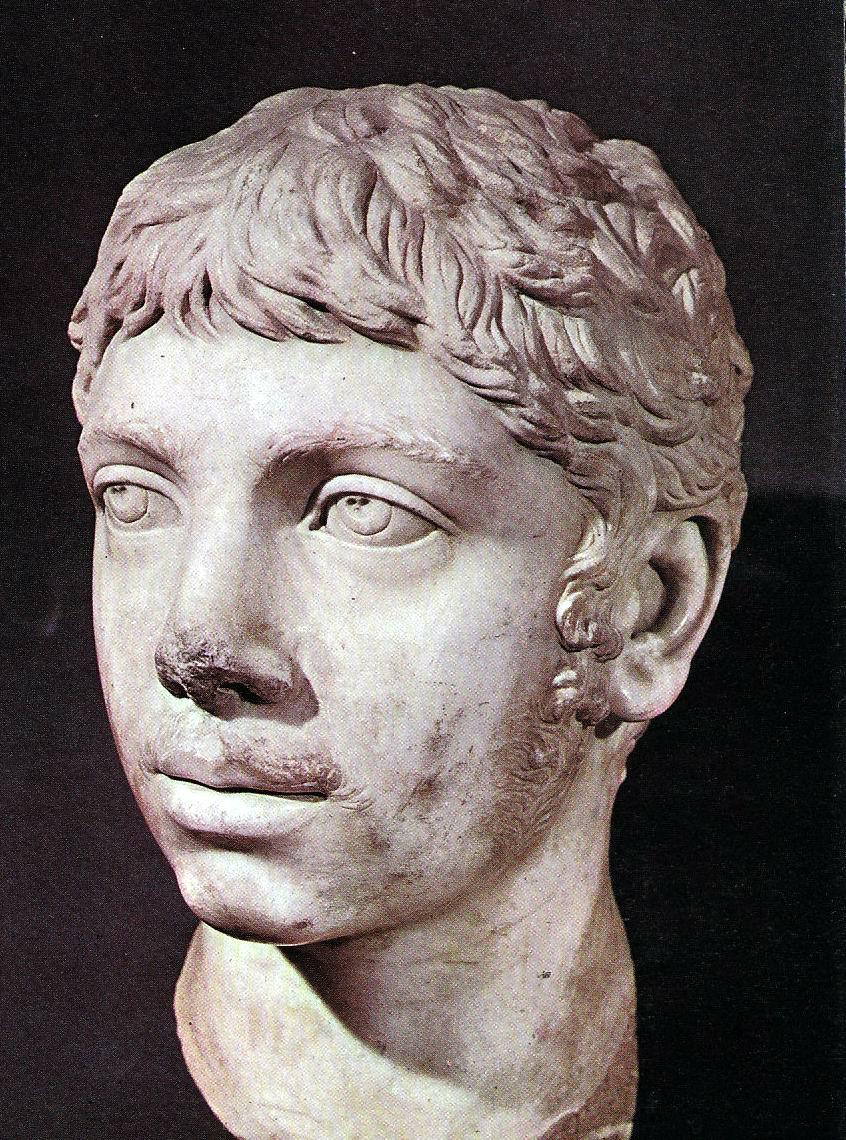

To discuss Elagabalus, one thing must be noted before all other things; there are almost no reliable accounts of her life. An empress who quickly became known as one of the most reviled leaders in the Roman Empire has a lot of different sources saying a lot of different things about the reign of a bisexual transgender empress from the years 218 to 222.

From the very beginning of Elagabalus’ reign, things were complicated. She only became empress because her grandmother started a rumour that she was the illegitimate child of the previous leader, Marcus Opellius Macrinus, who had been overthrown to get Elagabalus on the throne. Macrinus had replaced the former leader, Caracalla, after he was assassinated. To take Marcus’s place, Elagabalus had the help of her mother, her grandmother, and her grandmother’s friend/lover/servant, Ganny, who may have also been a eunuch. After they successfully killed Marcus, Elagabalus may have also killed Ganny when he advised her not to draw too much attention to herself. Elagabalus would ignore that advice for her entire life.

Another thing worth noting is that Elagabalus came into power when she was fourteen. Part of the reason why people followed her so easily was because of how highly sexualized young boys were at that time and in that culture. Though Elagabalus would later make it clear that she was a woman, society saw her as a young boy and sexualized her as such. Because of this, the amount of agency Elagabalus had when making large decisions is questionable at best. Much of her bad behaviour may be better understood in the context that she was a fourteen-year-old with the power most grown adults can’t handle.

But, that is an explanation for her bad behaviour, not an excuse. And there is a lot of bad behaviour to explain.

Unfortunately, here is where accounts become unreliable. Elagabalus was an empress whose first political move was to make her grandmother a senator, appointing the first female to the Senate of an incredibly sexist society. While by all accounts her grandmother was pretty great at her job, it was not a popular move and it undoubtedly caused a lot of resentment; resentment that may have been expressed in spreading gossip about Elagabalus to make people hate her and eventually overthrow her. And there are wild rumours, such as the one that claimed she drowned dinner guests in flowers, or that she served people her feces when inviting them over.

When looking at her life it can be very difficult to tell fact from fiction, but there are a couple of things most sources seem to agree on. Elagabalus was raised, for the most part, in Syria and when coming to Rome to rule, she brought many Syrian customs with her: wearing silk instead of wool, worshiping and forcing others to worship Baal and trying to demote the Roman god Jupiter, and wearing robes that were more similar to dresses. She also married five times, once to a Vestal Virgin, which caused an uproar in all of Rome as that was highly forbidden. The general punishment for having sex with a Vestal Virgin was having the Vestal Virgin buried alive.

Shortly after their marriage, the woman killed herself, reportedly because of something the empress had done. It is also generally agreed that Elagabalus had sex with a lot of people from many different genders and did not try to keep this a secret. She demanded everyone call one of her male slaves “the empress’s husband”. She would have sex with other people and then make her slave beat her as wives were beaten after being caught having sex outside of the marriage. One might, of course, mistake this for a heterosexual transgender woman, but her bisexuality is made very clear by her many wives, and the fact she had a chariot made that was pulled by naked teenage girls.

All of this upset the Roman public further, and she slowly lost her initial popularity. Leading to more murky events from questionable sources. The idea that she tried to pay a surgeon to perform a rudimentary version of gender confirmation surgery is one of the more popularly held beliefs, but it's largely based on gossip and speculation. It is possible that with her demanding to be called an empress, wearing make-up, and often disguising herself as a female sex worker, people wanted to add to the rumour mill that surrounded her transness. Regardless of whether she was searching for gender confirmation surgery or not, she was transgender. Though it was not unheard of at the time to be transgender, Roman xenophobia and racism attributed her femininity to Syrian stereotypes, as femininity was among the highest insults to the Romans. In regards to her gender, it can become difficult to parse the truth from the gossip. What can be said is that it is unlikely the gossip came from nothing, making it more likely that much is an exaggerated caricature of what actually happened.

There are also rumours that had nothing to do with her gender and were instead about her wild dinner parties. There are stories of wild animals being released, dinner guests being strapped to the water wheel and drowned, and foods like parrot heads being served. She seemed to enjoy the drama surrounding being in public office. Though her grandmother made sure that her political decisions were solid, her penchant for scandal would be her undoing.

Her upset of the Roman religious system, her dramatic antics, and her habit of killing people who disagreed with her built into resentment on an institutional scale. By the time she was eighteen, she was killed along with her mother.

Elagabalus’ grandmother soon noticed Elagabalus’ unpopularity and convinced her to adopt another one of her daughter's sons as an heir. Once that was done, it set into motion the overthrow of Elagabalus. Elagabalus’ mother stayed by her side throughout the political unrest and was killed alongside her. Elagabalus and her mother had their heads cut off, Elagabalus was killed in a latrine and her and her mother’s bodies were dragged through the streets before being weighed down and thrown into the river.

Elagabalus died at eighteen, after ruling for only four years. After her death, the Roman Senate had her erased from the history of Rome, which is a part of why information about her is so scarce and often so unreliable. What is known is that Elagabalus wasn’t a good leader, and probably not that great of a person either. But it is also known that she was a teenager.

Having both facts in mind, it becomes difficult to pin down exactly how Elagabalus should be remembered. Though she was undoubtedly worth remembering, she may also be one of the people in the queer community’s history that isn’t deserving of any reverence. She was queer, and she was also a very violent and justifiably hated person, but her bad behaviour was not because of her queerness. It is far more likely that her age played the biggest part in her terrible decisions.

John Edale from the Good Men Project brought an interesting perspective on this saying:

“But what should our own verdict be on [her]? Does Elagabalus deserve to be more widely or favourably remembered today? One could perhaps single out as admirable [her] determination to be as open as possible about [her] sexuality and about [her] own perceptions of [her] gender. But what of [her] equal determination to enforce [her] own religion, or [her] habit of having [her] critics murdered, or [her] attempts to dispose of the young Alexander? . . . Personally, I like just knowing that there were people like Elagabalus around. I like stumbling across them in corners of history where they were not expected, regardless of whether or not a case can be made for them having lived inspirational lives.

. . . Fundamentally, Elagabalus’s trajectory as emperor was determined less by [her] gender and sexuality than by the fact that [she] was a spoilt teenager who had suddenly found [herself] to be in possession of absolute power. Like Caligula, Nero and Commodus [she] paid the inevitable price for being no good at a job which [she] should clearly have never been given. In this respect at least, there was a certain tragic normality to [her] reign, and any history that finds a more prominent place for the Empress should perhaps also find a place for that fact.”

And there is no doubt that much of this is true. Not everyone in queer history is going to be easy to like, but that shouldn’t mean they are ignored, but it also shouldn’t mean their mistakes are erased. Because if the queer community can’t accept and face mistakes in the past, how will it learn how to face them in the present, or future?

Just like life, history is not meant to be simple, and it is important not to ignore facts or even possibilities for the sake of simplicity. Instead, it’s possible to embrace and explore the complex, even when, like Elagabalus, it is a bit messy.

[Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material.]

“Elagabalus.” Elagabalus, Illustrated History of the Roman Empire, www.roman-empire.net/decline/elagabalus.html.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Elagabalus: Roman Emperor.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Wasson, Donald L. "Elagabalus." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 21 Oct 2013. Web. 25 Sep 2017.

Weingarten, Judith. “The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor.” The World Rankings, Times Higher Education (THE), 22 May 2015.

Mijatovic, Alexis. “A Brief Biography of Elagabalus: the Transgender Ruler of Rome · Challenging Gender Boundaries: A Trans Biography Project · Outhistory.org.” Out History, The Digital Humanities Initiative.

Meckler, Michael L. “Elagabalus.” De Imperatoribus Romanis, 26 Aug. 1997.

De, Arrizabalaga y Prado Leonardo. The Emperor Elagabalus: Fact or Fiction? Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Edale, John. “Rome's Forgotten Empress: The Strange Reign of Emporer Elagabalus.” The Good Men Project, 6 Feb. 2015.