Madame Satã: The Ultimate Queer Archetype

“I’m going to explain you something: God gives the cold according to the coat. If I were an intellectual... Is it pronounced like that? I don’t know how to say this stuff. God said: you do your part then I’ll help you. But God didn’t help me because he knows that if he helped, I’d sell the world with his money.”

— João Francisco dos Santos, in response to the Pasquim interviewer's comment that if he were literate, he would’ve been a leader.

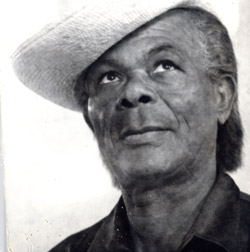

From the smoldering lands of the Northeastern coast of Brazil to the glamorous city of Rio de Janeiro, there’s no more appropriate itinerary for João Francisco dos Santos, better known by his drag persona Madame Satã, or Madam Satan. His fiery and controversial personality not only served as a muse but as a living and walking affirmation against oppression and those who want, without rest, to destroy beautiful things.

Defining Madame Satã as a drag queen is difficult because he was much more than an entertainer; he was father, a husband, an artist, and one of the earliest examples of a true queer activist who was always there to defend and protect, not only fellow queer people but also sex workers (mostly women), black people, the poor and disenfranchised. We will take a look at the scandalous and tumultuous life of one of the most powerful incarnations of not only Rio de Janeiro’s queer culture but Brazil’s.

The first thing to consider was the country’s social context in the first half of the 20th century. Francisco was born in 1900, 12 years after slavery was abolished along with the monarchy (the only one in the Americas). At the same time, a massive flux of freed black people and European immigrants decided to make Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the young Republic of Brazil, their home. Of course, with that comes a whole new set of challenges, such as insufficient sanitation and irregular housing. To deal with such a situation, the then president, Rodrigues Alves appointed Pereira Passos, an engineer, as the mayor of Rio.

Inspired by his stay as an engineering student in Paris, Passos attempted to civilize Rio with the construction of lavish boulevards, sewage systems, and ornamental gardens. Nevertheless, this Eurocentric pursuit to sanitize Rio wasn’t just about its physical structure, but also its people.

Besides heavy taxes on the poor and establishing ways of depriving the working class of their methods of subsistence (such as urban farming), the administration of Rio also saw as inappropriate the expressions of Afro-Brazilian culture, such as Candomblé, an Afro-Diasporic religion. The city of Rio was then transforming itself into a laboratory of social inequality, where a white elite would impose its ideas of beauty and civilization on to the general population, which was extremely diverse and made up mostly of black and mixed inhabitants.

A slew of the city’s excluded individuals went to live and work in Lapa, a bohemian neighbourhood in the city’s downtown where brothels, nightclubs, and bars converge. Home to a bustling scene of artists and intellectuals, it quickly became a queer resistance meeting point.

This would be the Rio de Janeiro that Francisco would have to face as a small boy at the time of his arrival from his hometown in the Northeast region of the country, known for its droughts, poverty, and sturdy people. Consistently, he chose Lapa as his home and despite being very young, Francisco did a lot of small jobs in and around his neighbourhood, mingling with sex workers and criminals. These were truly formative years that played an important part in building his assertive personality.

Even before adopting his “Madame Satã” persona, Francisco was already well known by his peers. In 1928, he went to live in a new pension where he’d perform drag routines, often impersonating Carmen Miranda. However, what would really start bringing attention to him would be his involvements with street fights, mainly with the police and random homophobes. He’d often ask the police officers to stop harassing the citizens, who were poor and didn’t have any kind of documents, and in return, he would get punched. Little did they know that Francisco was more than able to defend himself.

Then, the people of Lapa started seeing him as their own personal protector, frequently employing him as the bouncer of several cabarets and clubs. He would always be the one to act against police brutality whose modus operandi was the same as today’s: aim for the black, the poor, the queer. This fame would finally culminate in his first murder charges, in 1928, when he shot a city law enforcer, for reasons unknown to this day. Naturally, he went to prison for the first, but definitely not last, time.

He would stay in prison until the late 1930’s, just to witness a country whose social situation was far from ideal. Getúlio Vargas, quasi-fascist administration of the Republic, abolished political parties and syndicates, made up conspiracies to stay in power, and censored media. Eugenic attitudes by the white elite of the country started much earlier in Brazilian history, but they remained widespread until the end of Vargas’ administration.

Vargas' ideals were strongly linked to moral purity and strong work ethics, incompatible with the “undesirables” Francisco represented. We can’t say that the state was officially persecuting queer people since Brazilian mainstream society was extremely conservative and the mere mention of the word “homosexual” was utterly unthinkable, but these ideologies were still used to target us, under the guise of “erasing social problems”. Paradoxically, it was during this time that Francisco flourished.

During Brazil’s Carnival season, there are huge street parties where every inhibition is left at home. Naturally, it was a very important time for the queer community in the Marvelous City, more specifically during the so-called “Caçador de Veados," one of these parties and also an extremely influential queer event. “Veado” is a common pejorative slur used against gay men in Brazil and “caçador” means hunter in Portuguese, to give an idea of the irony present in the title. Nowadays, “veado” is being reclaimed, and maybe this event had something to do with it.

Although “Caçador de Veados” happened traditionally on the street, its organizers also did costume contests at a theater called Teatro República, now sold and under a different name and function. Fresh out of prison, Francisco couldn’t deny such an opportunity and competed in the event. Inspired by the vamp character in the Cecil B. DeMille’s movie “Madam Satan”, he mesmerized the audience dressed as this gorgeous demonic entity, scandalously showing to the general society that it was useless to retain such an unstoppable force. That day, Francisco was left behind, and Madame Satã was born, proving once again, through winning the contest, the Phoenix-like ability of the queer community to renew itself.

Madame Satã would continue to participate in such events, even though clashes with the police wouldn’t stop. His life became a succession of getting out of prison and then getting back. Needless to say, he made a name for himself both in the nightlife and in the criminal one, since even in prison he wouldn’t stop performing. He was imprisoned for 27 years in total.

In the late 1950’s he started to settle down. His beloved Lapa started to lose its prestige to other emerging bohemian spots, such as famous Copacabana. The political environment also got worse, with the military dictatorship making its way into the high ranks of society. Quite unexpectedly, he married a woman, although it was a purely platonic relationship, moved to the island where the prison he stayed in was located, in the outskirts of Rio, and helped raise six adopted children. In his old age, he became a cook, a very good one according to some people, and sometimes worked as a wedding planner. He acted in a few plays, mostly ignored by the press. He died in 1975 but, fortunately, symbols don’t ever really die.

If you pay close attention to the current situation of Brazil, you’ll notice that few things have changed despite the last decade of small but important social advancements, such as same-sex marriage. In the last few years, we’ve been experiencing a surge in conservatism, followed by an increase of an already high number of murders of both homophobic and transphobic nature. Madame Satã shows us we shouldn’t be afraid because ultimately he lived through even more bigoted, autocratic governments and still shined.

He played a role in Lapa that goes much beyond the physical boundaries of the chaos that is Rio de Janeiro. Everything merged into him: gay in a Catholic society, black in a former slave colony and not even working class, but completely outside of mainstream work, a lumpen. Glamorously feminine and yet, impulsively masculine. Nevertheless (or by virtue of), his people, the excluded, still chose him as their front man. He was the most absolute queer archetype of our culture.

Let us remember the original definition of queer: strange, something that lies outside of known pathways and it’s incredibly liminal and unrecognizable. Madame Satã is the epitome of the stranger, the messenger that travels between intersections. His existence was the perfect example of how this oppressive binary thinking we live under today isn’t capable of eradicating what makes us, human beings, as multicoloured and vibrant as a rainbow in the blue sky after a devastating storm.

[Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material]

PASQUIM. Madame Satã interview. Rio de Janeiro. May 1971

http://www.tirodeletra.com.br/entrevistas/MadameSata.htm

GENI MAGAZINE. Muito prazer, Madame Satã.

http://revistageni.org/11/muito-prazer-madame-sata/

LACERDA, Paula. O barão da ralé: o mito da Madame Satã e a identidade nacional brasileira.

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-73312005000100009

SILVA, Aguinaldo. Interview with Madame Satã.

http://coachdeatores.blogspot.com/2011/08/madame-sata-ultima-entrevista.html

CORTI, Ana Paula. Estado Novo (1937-1945): A Ditadura de Getúlio Vargas. https://educacao.uol.com.br/disciplinas/historia-brasil/estado-novo-1937-1945-a-ditadura-de-getulio-vargas.htm

About the author

You can follow Anghel Valente at @a.valente.ufo on Instagram.