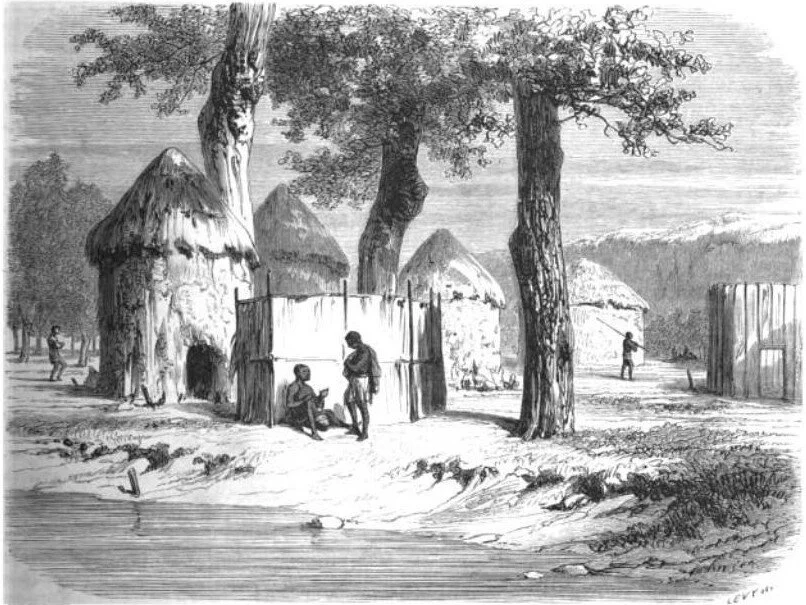

Drawing of Nuer village

Content warning for colonization

The Nuer people have a tradition of allowing infertile people with uteruses and people who have given birth to multiple children, have acquired land, and live independent of their husband to transition into "social men." Discussions of historical same-sex marriages and the ahistoric nature of binary gender roles pushed during the European invasion of other continents often include this tradition.

The social context and current consequences of these traditions are often left out, unfortunately. It is noteworthy that the Nuer did not have a centralized government for much of their history. Their society relied primarily on stable networks of social organization. With this, they would remain a strong force in what is now known as Southern Sudan and parts of Ethiopia. They lived a pastoral and largely nomadic lifestyle, moving regularly according to what was best for the people and what would keep the cattle fed and safe.

Much of Nuer culture revolves around the care of cattle and maintaining strong bonds within a family. These families' roles were specifically adapted for an economic system based in direct labour rather than wage labour. The place of people assigned female at birth in this system was varied.

Whereas men were largely given work that demanded movement, the women generally worked with things within their home and communities. This meant daily care for the cattle, making beers, tending to gardens, caring for and educating children, and giving birth to those children. The birth of children was, in fact, an essential and respected job, one that would seal a marriage. A married couple would only begin living together after the birth of the first child. The birth of the third child would cement the birth giver's place in their new family.

In general, the birthing process was a respected one. The people giving birth were given protections precisely because of this—one of these being a year between giving birth and the return to sexual activity. While more children were seen as better, more children would not exist without the people giving birth's continued health.

The difference between direct labour and wage labour has a significant impact on how different forms of labour are valued. With wage labour, as popularized by capitalism, only specific jobs are compensated. Generally, the jobs that receive payment are those done outside the home and family. An example of this is how a person is generally not paid to clean their own home but is paid to do the same amount of work in someone else's home.

In this system, social worth and economic worth become more important than any other kind. While the reality is that some of the most important jobs remain unpaid, they are seen as less important or worthy by most societies that rely on capitalist economies to define worth.

With direct labour, the job's value is determined by how it affects the person or community. The job is paid by what it produces rather than by money. Because money has been taken out of the equation, the reward for cleaning your house is having a clean house. The reward for giving birth is then in the children and what they grow up to do. There are many tasks that young children are put in charge of. Because children, like women, are generally expected to stay home, the tasks they assist with bring a direct benefit to the person who gave birth to them. When the children grow up, there are direct benefits to the person who raised them. With children assigned female at birth, the benefit is often the brides-wealth paid in cattle. With children assigned male, it is their continuing family legacy and the possibility of raising their social status.

Because the Nuer economic system was built around direct labour rather than wage labour, the work that goes into being pregnant, giving birth, and raising children was treated as equally important to other forms of work.

Thus, the social roles of gender were deeply wrapped up in the job of caring for children; women were required to stay close to the community and complete specific tasks because those were the jobs that made the most sense in concert with the raising of children.

When a person assigned female at birth was infertile, there was no reason for them only to do the jobs of and fulfill the roles of women. Because of this, it was a common and well-known practise up until the 1930s for people assigned female at birth to transition into becoming a "social man" and marry a woman.

It is here that the term queer must be questioned in its application to the situation. If the term queer is defined by a difference from the norm in relation to sexual and gender identity, then it would be wrong to apply it to the Nuer men who had been assigned female at birth.

If it is understood and respected that while the queer community is not a monolith, it has some base shared experience that the word becomes relevant.

If the "queer experience" is defined by discrimination, then the Nuer men in question would not fit within it. If, instead, the "queer experience" is defined as a large network of incidents, questions, identities, and experiences that overlap, then they would.

A woman can still be seen as a woman without experiencing sexism (or the same version of sexism as other women), as there is still an underlying layer of shared experiences and realities that comes with identifying as a woman. While few singular realities are universal, the unique collection of realities that every individual woman has can be a tie to connect her to the grouping of womanhood. Even if the only thing a woman has in common with women as a group is self-identifying as a woman, that is enough.

If the only thing the Nuer men have in common with other people who were assigned female at birth and then transitioned is the base experience of being assigned female and that changing later in life, is that enough?

Queer is not the perfect word to describe the Nuer tradition of infertile women socially transitioning into men. However, it may be one of the better options available. To call the social men transgender would not be entirely wrong, but would not take into account their own definitions of themselves. While many of the people who were in this situation may have identified more with being a man than a woman, for some, the difference was most likely social and economic. That being said, calling the marriage of the person in question to a woman a gay marriage fails for the same reason. This is the issue with binary applications of gender and sexuality. While some may have still identified as women, others may not. The term queer works because it allows for the complex reality.

It would be difficult to pin down what every social man felt about their gender. Though the Nuer had a rich and thorough system for keeping oral history, much of that was destroyed by colonial powers. Queer allows for a wide range of experiences.

It seems only fitting to recognize that the Nuer tradition is slightly more complex than most sources discuss. As well as infertile AFAB people being able to transition into men socially, AFAB people who gave birth to many children and owned property independent of their husbands were also allowed to participate in the tradition.

For the people experiencing infertility, there are additional possible benefits to the transition. Infertile people were sometimes seen as divine beings, and many social men would become healers for their community. Some also accrued property, cattle, and respect from the community. This would also lead to them marrying multiple women, as was common for men in the culture.

As for children, a social man would generally choose someone as a sperm donor, and that person would have no rights to the child themselves. Despite this, many families would keep the person in the child's life in small ways, such as inviting them to weddings. Though the relationship between the biological father and child was slight, it could solidify a relationship between two families or villages.

By all accounts, the social men were accepted wholly as men by the community. They would be allowed to go to ceremonies only for men and do tasks generally done by men. For the social men who had given birth and acquired property, their husbands (if alive) referred to them as "brother" rather than wife.

With a complex web of community and kinship, the Nuer people were well-known for having a strong sense of solidarity. Though the Nuer would travel in smaller groups, they would collectively mobilize upon outside aggression and soon became well known by colonists as a force to be reconned with. Every step England made to colonize them produced intense backlash as they protected themselves and their way of life.

In the 1930s, England deployed airplanes to firebomb Nuer villages and sacred sites. From the ground, they stole Nuer cattle. They described it as an "experiment in the pacification of primitive peoples." However, it was a direct attempt to force the Nuer people to pay taxes to the English government in reality. Even with these attacks, they never successfully forced the Nuer people to pay for their own colonization.

When they were eventually forced to pay taxes and participate in the Sudanese capitalist economy, the government did an exemplary job of proving every fear the Nuer had correct.

The justification for most forms of taxation is the redistribution of resources—giving the government money to build infrastructure and keep citizens safe. Various governments have interpreted the idea of building infrastructure and keeping people safe in different ways, many in thinly veiled attempts to accrue personal wealth.

Despite the insistence that they pay taxes, the various governments that tried to rule the Nuer made it very clear they were not interested in building infrastructure or keeping Nuer people safe. In her paper "Nuer Women in Southern Sudan: Health, Reproduction, and Work," Ellen Gruenbaum discussed her view of the situation during her time in the Nuer region in the 1970s, writing:

"Thus the health services that did exist had by the 1970s done little to relieve the high mortality rates resulting from the area's health problems. In fact, the government gave so few services of any kind that it is not unreasonable to argue that the government had maintained this region, in effect, as a labor reserve rather than an integrated part of Sudanese society."

The forceful introduction to a money-based system has caused untold trauma to Nuer people individually and collectively. Moving from a society that did not have comparable transactions to one that required them led to a massive difference in generational wealth. Even with the payment of taxes, many Nuer attempt and succeed at keeping more traditional structures within their communities. This does not come without a massive cost.

Still required to pay taxes, many were forced to move into cities. Though some had aspirations of making money and returning home, many were unable. Most high-paying jobs required a specific education that the government was not putting money into, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the Nuer people to receive those qualifications. The education passed from generation to generation was not well respected and had been damaged by various government attacks on the Nuer people.

This also brought a shift toward European gender roles. While men were freer to leave their communities to find work, women's work was still essential to daily life and restricted their ability to leave. While still performing traditional roles, women's ability to be independent has drastically diminished. Under a capitalist system, their work can be largely described as invisible labour. Both economically and socially, their work is largely ignored. Still required to pay taxes, the women often need to marry. Despite having more economic and social power, men still rely on the invisible labour done by the women in their lives.

Capitalism has also entered other areas of the Nuer lifestyle. Though there had once been a cap on brides-wealth, the amount of cattle given to the bride's family is now competitive. This makes much of life more difficult and dangerous for Nuer people. Things like cattle raids, both being performed by and perpetrated against Nuer people, have become increasingly violent.

Traditions that were built around the existence of an entirely different economic system can become ways to hurt people within a community; while the traditions like that of the Nuer's "social men" fall to the wayside, both due to damage from Christian missionaries and the colonial changes to gender roles.

That being said, capitalism is not the only force at work. With the continuous change and violence, feuds between different groups have become more intense, leading to harm done to and by the Nuer people. Ellen Gruenbaum wrote of this:

"Prolonged tension and war are inhibiting the chances of improvements in living conditions, not only because of the loss of lives and insecurity, but also because of the undermining of the pastoral economy by the capture and confiscation of cattle as well as population displacement, the disruption of employment opportunities, services, and supplies."

In her paper "The Return of Displaced Nuer in Southern Sudan: Women Becoming Men," Katarzyna Grabska writes about the effect displacement has had on the Nuer women. In one telling passage, she writes:

"A few months after her return to Ler, with the help of relatives, Nyakuol had built a house, started a business in the market, sent her children to school and started to cultivate land. Her neighbours saw her house (cieng Nyakuol)as a sign of her settling in. One of Nyakuol's friends, Kuok, a young man in his late twenties who had also returned to Ler, told me: 'Look at Nyakuol, she is like a man now. She can take care of her own cieng(family/home), she even brings food home, and she has a business. She is also a leader among the women. She has the strength of a man. Women are becoming the real men in Southern Sudan now'"

It is clear that despite attacks on many sides, women and AFAB Nuer are by no means a beaten-down group. They continue to fight and work to balance progress and tradition.

Some do this by leading their community, others by supporting their community. Though the invisible labour done by many Nuer has been devalued, it is necessary, and solidarity within Nuer communities has not gone away. Nuer people have experienced more than their fair share of conflicts both within and outside of their country.

Katarzyna Grabska writes:

"Decades of fighting, violence, looting and displacement left communities who had stayed behind impoverished. In this context, return was a challenge. The narrative of Nyakuol, who we met in the introduction, presents some of the initial difficulties faced by returnees: When we arrived here, there was not much [government] support. I had to rely on my family[for support]. At the beginning I was very happy to be back. I was with my family whom I had not seen for over ten years. But things are getting difficult. I am very unsettled. Our life here is hard because we have no money. Now, in Sudan, if you have no yiou (money), you cannot get food. Everything here is about money. I want to first nyuuri piny (settle down)— to have a permanent land and du ̈el (house) — and then I need a job. In Kakuma, I used to work with IRC (International Rescue Committee) as a midwife. I have all my certificates from courses that I took in Kakuma, so this might help me to get a job. As a widow, I have to rely on myself to provide for the family. No one else is going to help me."

Organizations like Nuer Development Association are working to empower Nuer people directly to help recover all that has been taken and lost. A grassroots organization that works directly to stop gender-based violence, the Nuer Development Association describes this mission:

"The culture of subjecting women as subordinate and considered as a property is our prime objective to stop as an organization. These are wide range issues like gender-based violence and its harmful practice in the Nuer society. As an organization dedicated to moving beyond barriers, and fight this vices and prejudices harmful practice, the following strategy is carried out to combat this uncivilized practice.

Educate the public in regard to violence against women and harmful traditional practices so as to improve gender equality, reduce gender-based violence and harmful traditional practices that are widely practiced in the target Woredas."

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Grabska, K. (2013). The Return of Displaced Nuer in Southern Sudan: Women Becoming Men? Development and Change, 44. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12051

Gruenbaum, E. (1990). Nuer Women in Southern Sudan: Health, Reproduction, and Work [Working Paper, California State University, San Bernardino]. https://gencen.isp.msu.edu/files/4814/5202/7049/WP215.pdf

Hutchinson, S. (1962). A Guide to the Nuer of Jonglei State. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hutchinson, S. E., & Pendle, N. R. (2015). Violence, legitimacy, and prophecy: Nuer struggles with uncertainty in South Sudan. American Ethnologist, 42(3), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12138

Krige, E. J. (1974). Woman-Marriage, with Special Reference to the Louedu—Its Significance for the Definition of Marriage. Africa, 44(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/1158564

Lacey, E. (2013). It Takes Two Hands to Clap: Conflict, Peacebuilding, and Gender Justice in Jonglei, South Sudan [Dissertation, University of Cape Town]. https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/3730/thesis_hsf_2013_lacey_elizabeth.pdf?sequence=1

Launay, B. R. (2015, May 13). Is same-sex marriage anything new? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2015/05/13/opinions/launay-same-sex-marriage-history/index.html

Lévi-Strauss, C. (2013, April 1). Parenthood Revisited (J. M. Todd, Trans.). Harper’s Magazine. https://harpers.org/archive/2013/04/parenthood-revisited/

O’Neil, D. (2006, June 29). Sex and Marriage: Marriage Rules (Part 2). https://www2.palomar.edu/anthro/marriage/marriage_4.htm