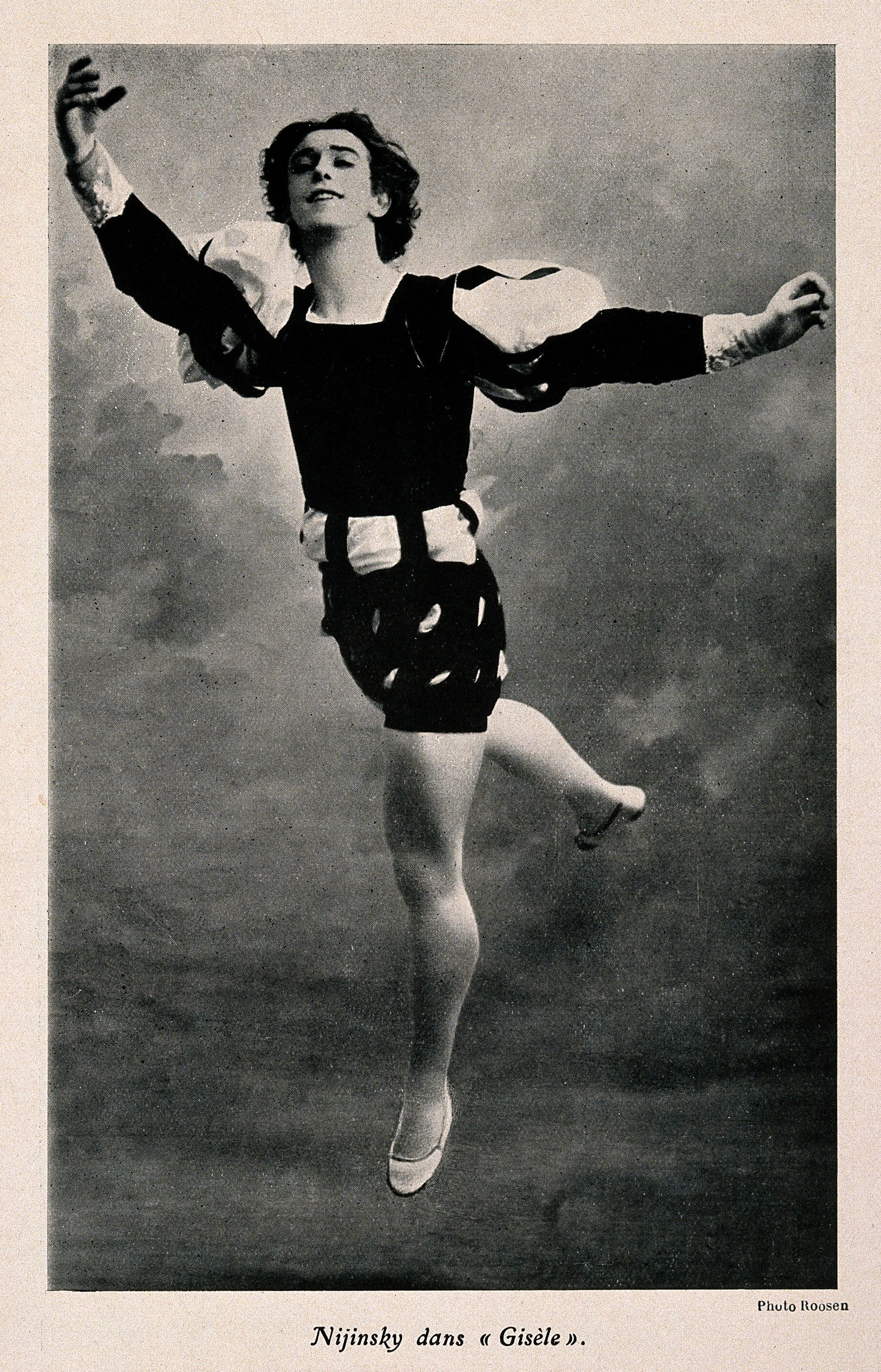

Vaslav Nijinsky, a white ballet dancer with medium length dark hair, in a scene from G̀isèle'. He is posed with one leg back in the air and both arms up. He smiles with his eyes half closed.

Content warning for institutionalization

“You will understand me if you have seen my dance.”

– Vaslav Nijinsky

There are no videos of Vaslav Nijinsky dancing. Known as one of the best dancers to ever live, the lack of footage was a choice made, as video recording equipment at the time was jerky and the quality could not be guaranteed. His dancing is conveyed mostly from memory, people telling of the times he flew on stage, the riots over his movement, a word often used is angular. There are photos of him posing, both in costume and out, and there is a certain charisma there. Even in stillness, he has a kinetic energy to him.

The son of two dancers, this isn’t entirely surprising. Born in 1889 in what is now Ukraine, he was very much raised to become a dancer, as were his siblings. Throughout his story, the three elements of luck, talent, and desperation are braided tightly together. From a young age, he was not only picked out as someone with a natural aptitude for dance but he was also made very aware that his future in this field could be what stood between his family and destitution. As his father had left his mother to fend for herself and her children, he and his siblings lived in relative poverty. Settling in Saint Petersburg, Vaslav’s mother was able to use her connections in the dancing world to get her son, and later her daughter Bronislava, into the Imperial Ballet School.

Bronislava and Vaslav would go on to develop a close bond, both admiring and pushing each other to professional success. When their time in the Imperial Ballet School overlapped, the two would spend nights discussing ballet and rehearsing together. Their paths began to diverge as the graduation approached, with Vaslav gaining more and more acclaim - even being offered a place in the Imperial Ballet Company. While some of his time in school had been marked by his inability to focus on anything that didn’t interest him, he still chose to complete his studies and graduated second in his class.

Encouraged to seek out a wealthy patron, this was Vaslav’s first taste of financial success and was a stepping stone he used to pull his family out of poverty with him. All throughout his career he would try and maintain financial support for his mother. Still, his position was precarious, and when at 19, he was approached by 36-year-old Sergei Diaghilev, the two would begin a relationship.

While an age gap in a relationship is not in and of itself a negative thing when both parties are of age, which both were in this case, the power dynamic is worth considering. Especially, when as in this case, the power dynamic is increased by a class and social difference with Sergei being a wealthy nobleman who was incredibly powerful in the ballet world. After what many people believe was an orchestrated plot from Sergei to get Vaslav fired from his job with the Imperial Ballet, Sergei would hire Vaslav into his own ballet company.

Now his boss, as well as partner, Sergei’s relationship with Vaslav would be remembered as fraught by both parties. While Vaslav was known for being a rather quiet man off-stage, he was also well known for fluctuating moods, something that was later linked to mental illness. His closest relationship was with his sister, who shared Vaslav’s interest in choreography, and though she was arguably more successful in that domain, the both of them began making names for themselves.

In 1913 Bronislava was unable to tour with her brother, as she was pregnant, and when Sergei decided not to join the company on the boat to South America, Vaslav was left without the two people he was closest to. Romala de Pulzky was one of the people who were going on the tour, a rich aristocrat. She had seen Vaslav in a performance and become infatuated. Paying to practice with him, she was unable to attract his attention after he realized she was not really a dancer. On the boat trip, the two would need a translator to speak to each other as they didn’t have a language in common, and when Vaslav eventually proposed, Romala would run away crying, as she thought he was playing a mean trick on her. After using a mixture of French and miming, Vaslav convinced her of his sincerity, and the two would get married soon after.

This development would enrage Sergei, and the man would fire Vaslav from the ballet company. Vaslav was entirely blindsided by this and would try to start his own ballet company with the help and support of Bronislava, but while the ballet itself was successful, the company went under.

At the start of World War I, Vaslav along with his wife and child were in Budapest and put under house arrest as they were Russian citizens. This situation would affect his mental health, and being separated from the rest of his family would weigh on him through this time. It was Sergei as well as King Alfonso XIII of Spain, Queen Alexandra of Denmark, Dowager Russian Empress Marie Feodorovna, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, Pope Benedict XV and President Wilson, who would secure his release and return to ballet.

While he experienced some success in his return to dance, his mental health continued to decline, leading up to his last public performance when the pianist Arthur Rubinstein would cry at Vaslav’s obvious confusion. Though his brother had been institutionalized, and Vaslav was deeply afraid of the same fate, after consultation with Eugen Bleuler, Vaslav was diagnosed with the newly discovered schizophrenia and was sent to an institution. He would go on to interest and influence the medical world's understanding of schizophrenia, first within his life as he met with many of the influential psychiatrists at the time, such as Carl Jung and Sigmond Freud. He would also keep meticulous journals that would go on to influence understanding of schizophrenia long after his death. The journals were edited by his wife and she removed less flattering parts, discussions of his sexuality, and the more confusing bits.

The reality of the journals reveals a man who experienced an extremely troubled relationship with Sergei and had a deep abiding conviction that his job in this world was to dance and to love. The later half of his life was spent in a rotation of institutions, and journaling.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Bidart, F. (1981). The War of Vaslav Nijinsky. Summer 1981(80). https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/3235/the-war-of-vaslav-nijinsky-frank-bidart

Gay Ballet Star Vaslav Nijinsky: From Genius to Madness. (2019, March 27). Metrosource. https://metrosource.com/gay-ballet-star-vaslav-nijinsky-from-genius-to-madness/

History of Vegetarianism—Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950). (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://ivu.org/history/europe20a/nijinsky.html

Nijinsky on Nijinsky: The Decline and Fall of the Ballet Russes. (n.d.). Pushkin House. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.pushkinhouse.org/blog/2020/3/1/nijinsky-on-nijinsky-decline-and-fall-of-the-ballet-russes

Nijinsky, V., FitzLyon, K., Acocella, J., & Anders, J. (n.d.). Radical Shadows: Previously Untranslated and Unpublished Works by 19th and 20th Century Masters. Conjunctions. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24515902

Nijinsky, W., & Nijinsky, V. (1968). The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. University of California Press.

Research, R. B. (n.d.). Everything & More You Wanted to Know About Ballet. Russian Ballet Research. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://russianballetreasearch.com/vaslav-nijinsky

Schizophrenia and ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. (2019, March 6). OUPblog. https://blog.oup.com/2019/03/schizophrenia-and-ballet-dancer-vaslav-nijinsky/

Vaslav Nijinsky. (n.d.-a). American Ballet Theatre. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.abt.org/people/vaslav-nijinsky/

Vaslav Nijinsky. (n.d.-b). Legacy Project Chicago. Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/vaslav-nijinsky

Vaslav Nijinsky. (2016, May 12). Living With Schizophrenia. https://livingwithschizophreniauk.org/vaslav-nijinsky/

Vaslav Nijinsky: Creating a New Artistic Era. (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2022, from http://web-static.nypl.org/exhibitions/nijinsky/home.html

Vaslav Nijinsky: The Lost Legend Of Early 20th Century Ballet. (2021, March 12). https://www.balletherald.com/vaslav-nijinsky-lost-legend-20-century-ballet/

Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreographic score to the ballet L’après-midi d’un faune—The British Library. (n.d.). Retrieved May 27, 2022, from https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/nijinsky-choreographic-score

Victoria and Albert Museum, D. M. webmaster@vam ac uk. (2012, November 14). Vaslav Nijinsky. Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 2RL. Telephone +44 (0)20 7942 2000. Email vanda@vam.ac.uk. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/v/vaslav-nijinsky/