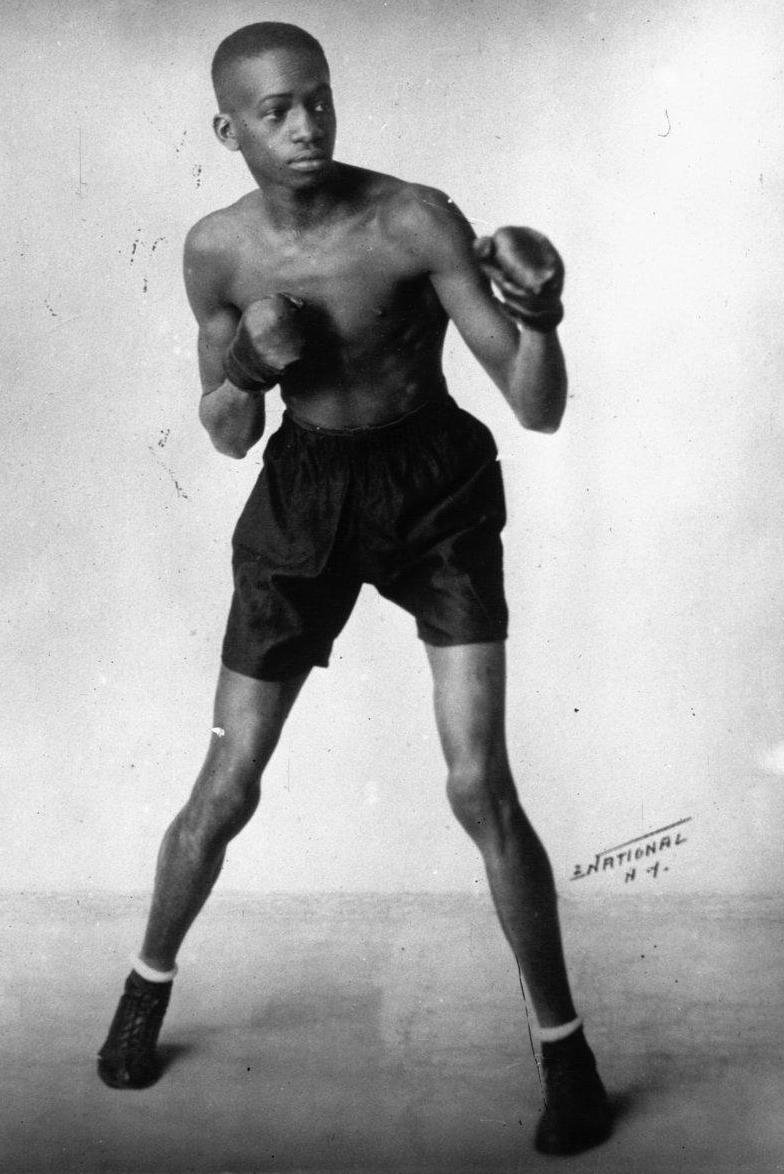

Alfonso Brown, a tall lean Black man stands in a boxer’s stance with his gloved hands raised. He wears black shorts and shoes. He wears a thoughtful expression.

“I don’t want to be touched, my wrists are made of glass, they’re as thin as yours.” – Al Brown

At 5’11” with a 76-inch reach, “Panama” Al Brown was one of the tallest and rangiest boxers in bantamweight history who died with a career of accomplishments that spoke for themselves but took a lifetime to achieve true recognition. Throughout his life, Brown pushed through adversity as a result of being Afro-Caribbean and the lifestyle choices that he made. Still, his skills and talent in the ring made it impossible for Brown to be ignored or erased, and via victory after victory he managed to win numerous championship titles and achieve numerous firsts in his sport of choice. With a life marked by constant tragedy and struggle, Brown persisted and pursued his dream job by day and the pleasures of life by night, ultimately living an unabashed and flamboyant life.

“Panama” Al Brown was born Alfonso Teófilo Brown on July 5th, 1902 in Colón City, Panama. His mother was a local Colónese woman while his father was an emancipated slave from Tennessee who escaped the Jim Crow South and fled to Panama to work on the Panama Canal. Alfonso’s father died suddenly when he was 13 years old, leaving his mother, who worked as a cleaner, and five siblings to sink into extreme poverty. To provide his family with financial support, Brown was sent to work as a young teen and ended up as a clerk for the U.S. Shipping Board at the Panama Canal Zone. It was there that Brown first witnessed American soldiers boxing with each other, and coupled with libidinous ogling, he carefully watched their every move and became enamored by the sport.

Wanting to learn for himself, Brown walked into a local gym and began to shadowbox and spar during his spare time. He soon found himself having amateur fights, and was nicknamed Kid Teófilo in the ring. Fueled by his family’s poverty and own grief, Brown soon won the national amateur championship. In 1922, at not even twenty years old, Brown officially turned professional in Panama, and had his first fight on March 19th, beating Jose Moreno in six rounds. After racking up another five consecutive victories, Brown ended the year with his seventh pro fight ever, where after 15 rounds with Sailor Patchett the match ended in a draw decision.

Having felt he achieved as much as he could in Panama, Brown chose to follow in the footsteps of other Panamanian boxing stars and sail to New York. Once there, Brown was billed as the “Champion of Panama”, despite never officially earning that distinction, and in 1923 had his first international fight in the Big Apple, a draw against Johnny Breslin. Brown returned home, but had impressed in the ring and was contacted by several industry men who convinced him that the in-ring earnings of the best boxers in the U.S. would be far greater than anything he could ever make in Panama. Brown then stowed away on a ship that was sailing from Panama to New York and officially relocated to the city to begin a new chapter and pursue his dream of becoming a professional athlete.

Rebilled as “Panama” Al Brown, the year 1924 saw the boxer pick up an impressive 11 consecutive wins before suffering his first loss against Jimmy Russo in December. Meanwhile, The Ring magazine already named him the 3rd best flyweight in the world and 6th best bantamweight. Brown picked up another 11 wins out of 13 bouts in 1925, and in 1926 fought for the first time in New York City’s esteemed Madison Square Garden, where he won in a third-round KO against Teddy Silva. Brown’s career and fame were skyrocketing, but with it came a rise in public scrutiny of his lifestyle, and Brown began to face criticism and derision for both his race and rumored sexual proclivities.

A cartoon at the time portrayed Brown as an unrivaled fighter, but in a racist and xenophobic fashion: Brown was drawn as a gangly ‘Sambo’ caricature surrounded by a bevy of short white contenders imploring him to leave the U.S. forever. Concurrently, rumors spread through Harlem that Al Brown was “in the life” and spent his free time frequenting the establishments of sexual deviants. In fact, Brown at the time was living not exactly out of the closet, but not quite in it either. On more than one occasion, Brown was told to “tone it down”, and at times he began to speak about having a girlfriend or a wife back home in order to keep up appearances. Nevertheless, the rumors persisted and Brown was banned from his gym and kicked out of his hotel, rendering him homeless.

While living on the streets, Brown went to meet with Eddie McMahon, the promoter and managing partner of the Commonwealth Sporting Club, and explained his situation. Brown and McMahon struck a new deal with Brown’s former manager and got Brown back into his hotel room. He also moved Brown to train at a new gym under the tutelage of Bill Miller. Brown trained hard under Miller, but over the next year became increasingly frustrated with the boxing industry in the States. It was evident to Brown that his race and the open secret of his sexuality continued to hold his career back, as he was repeatedly denied title shots and was instructed to intentionally avoid landing knockouts so white boxers would still fight him. Brown began to understand that in the States, the individual fighter meant very little in boxing and that he was just a pawn being used by the higher-ups for profit.

Struggling with these frustrations while trying to enjoy but conceal a gay lifestyle at night, Brown turned to drinking heavily. During one of his debaucherous evenings out, it was suggested to him that he would fare better in France. Brown, in need of a change of scenery and who had just received boos and racial slurs after his Madison Square Garden debut, had no reservations about leaving the city for good, and at the end of 1926 moved to Paris. Once there, he was much more welcomed as a Black man, and as Brown put it: “In Paris I spent my first night in Montmartre. In all those nightclubs where now everyone is my friend I went from discovery to discovery. Everywhere I encountered the same warm, smiling welcome, the same excellent champagne…everywhere my cap, my light beige suit, and my suede shoes made a sensation.”

1920s Paris was in fact a popular destination for Black entertainers, who were able to find more work opportunities and less overt racism, and for Brown—already quite the drinker and nightlife connoisseur, the City of Love’s many indulgences were quite alluring. He began to go out night after night and lead a dangerously extravagant lifestyle, once quoted proclaiming, “All I need to live is 20,000 bottles of champagne.”

Despite the late-night dalliances, Brown maintained his composure during the daytime and made a name for himself as a popular fighter in France. Training under Eugene Bullard, he debuted on November 11th, 1926 against Antoine Merlo where he ended the fight in three rounds with a KO. Brown followed up his first European victory with another, electrifying the crowd after KOing the never-before-KO’d fighter, Roger Fabregues. Brown made more money that night for a single fight than he ever had before.

With a boxing career taking off and newly acquired wealth, Brown became recognized in Europe for his flamboyant lifestyle, known for dressing elegantly, rumored to change outfits six times a day. He also purchased expensive vehicles only to dispose of them quickly and dabbled in the dangerous worlds of horse betting and gambling. After one fight in particular, Brown spent his entire earnings on a fancy Bugatti. When it blew up on its first voyage, he immediately went back and bought another one on credit. In addition to boozing all night at bars, Brown also became known for his interest in the arts and would spend much time attending jazz clubs and cabaret performances, oftentimes performing himself, and was considered by some to be the male Josephine Baker. Paris allowed Brown to feel more comfortable with his sexuality, and he began to live openly, frequenting popular gay spots like the Moulin Rouge and the Monocle.

By 1928, Brown had battled his way into a fight with Kid Francis for the vacated National Boxing Association’s bantamweight title, a match that was met with resistance. Francis, who had only lost three out of seventy-three fights, was heavily favored to win, but Brown kept him off guard and won in 12 rounds, making history by becoming the first Latin American boxer to win a world title in boxing. Almost immediately, several high-ranking NBA officials, who were against Al Brown fighting for the title from the start, met with the Association’s new president. A month later, the Association put out a press release that read: “In the previous list Al Brown was recognized as the bantamweight champion, but now that bantamweight championship is declared vacant.” No further explanation was provided.

1929 saw Brown nab a win by having one of the quickest KOs in boxing history. As soon as the bell rang, Brown knocked out his opponent Gustave Humery with the very first punch he threw, breaking his jaw. The match in total lasted fifteen seconds, ten of which were used for the KO ten-count. Fans who had barely blinked, let alone sat down, presumed that Brown had taken a cheap shot and began to boo and call him a cheater. 1929 also saw Brown win the NY State Athletic Commission world bantamweight title after defeating Gregorio Vidal in another historically significant victory. Yet again, Brown’s championship reign was met with controversy, and the NBA sent out another press release that stated they did not recognize him as bantamweight champion.

Despite these bureaucratic setbacks, Brown continued to hit his stride, winning 14 out of 16 matches in 1930, with the other two declared draws. On February 8th, he defeated Johnny Erickson to claim the NBA Bantamweight title again, and on October 4th beat Eugene Huat to claim the International Boxing Union title. After the victory against Huat, The Daily Mail published a cartoon of Brown titled, “The Shadow Man” with a caption that read, “Napoleon stirred uneasily in his tomb last night when Eugene Huat, a fighter of France, was beaten BY A COON.”

With two championships under his belt, Brown’s manager began to overbook him for bouts, and though Brown continued to rack up victories, the damage to his body began to take a toll. Meanwhile, Brown’s personal life and lifestyle also affected his well-being. In 1932, Brown’s mother passed away in Panama, and he tormented himself over not being there for her. Brown himself also contracted syphilis during this time, and soon thereafter began struggling with an addiction to painkillers. Thanks to his nightlife companions, Brown also discovered opium.

In 1934, the NYSAC suspended Brown for opting not to fight against Mexico’s Rodolpho Casanove. Shortly thereafter, the NBA stripped Brown of his title. Brown then ran into further trouble during a rematch with Humery, where he was disqualified in round six and accused of using illegal tactics. The crowd at the fight perceived that Brown was fighting the match drunk and began to form an angry mob. An assault ensued, and Brown was left beaten, bloody, and bruised by a slew of unidentified attackers.

After a few months of recovery, Brown managed to hold on to his IBU title until 1935 when he lost it to Baltasar Sangchili. Allegedly, Sangchili poured a narcotic into Brown’s drink before the fight, and only later did Brown learn that it was his own agent who had poisoned him after being bribed by the Spanish boxer. Still, Brown managed to last fifteen rounds in the fight before passing out, and Sangchili was declared the winner and new champion while the crowds celebrated Brown’s defeat.

After this loss, Brown decided to walk away from the sport. He fired all his handlers, retired, and went to perform in cabarets. He received a six-month offer to dance and sing to the National Scala in Copenhagen, but when the stint expired and the offer was not extended, Brown returned to Paris where he found work as a tap dancer and sax player at the Caprice Vennois. With his new career in nightlife, Brown spent many of his evenings at the bars post-performance, where he would continue to drink and smoke opium on a daily basis. As he continued to endure the effects of extreme drug use, one night at the Vennois Brown met a former-opium user, famed French poet, Jean Cocteau.

“When I met Al Brown he was stalled in a paste of fatigue and disorder,” Cocteau recalled. “A human rag” is how Cocteau described Brown, who was eaten away by opium, syphilis, champagne, and tranquilizers, but in the eyes of the poet was still “a black diamond in the rubbish heap.” An unlikely companion, Cocteau was an artist with little knowledge of the boxing world who had only heard the name Al Brown once in passing. But Cocteau, in recovery himself, recognized his younger self in Brown, empathized, and felt he could help the boxer win back his place and chase away his demons.

Cocteau began bringing Brown to dinner parties and social gatherings, and Brown, in need of a home, moved into a room in Cocteau’s hotel. The pair began an affair that was an amalgam of lovers, friends, and business associates, and Cocteau referred to his new lover as “a poem in black ink.” During a particularly erotic encounter, one evening Brown asked if he could bathe at his place, and when he got out, Cocteau went right in without changing the water. Brown was amazed that the writer would get into the bath immediately after Brown when most white people would have emptied the water that he, a Black man, had used. Completely smitten, Brown bent over and proceeded to kiss Cocteau’s feet.

During their time together, Brown began to confide in Cocteau, revealing to the writer that he believed he was poisoned by traitors, which led to his downfall. Inspired by the narrative, the writerly Cocteau convinced Brown that he must seek vengeance and recapture what was rightfully his. Brown initially refused, still disgusted by the violent sport and his experiences with rigged matches, spectators yelling racist and homophobic slurs, and angry mobs who nearly lynched him anytime he beat a white opponent, but over time, the persistent Cocteau convinced the boxer to clean himself up and give it another go.

Thus marked the peculiar beginning to one of the most amazing comebacks in boxing history, as most people believed Brown would never fight again, and certainly that Cocteau had no place as a boxing manager. Cocteau began by putting Brown through a rigorous detox, cutting him off from drugs, alcohol, and the outside world. Brown spent weeks suffering through withdrawal, and was then sent to a desolate farm in Aubigny equipped with a makeshift gym, and began training with Bob Roberts. After a two-year hiatus, Brown stepped back into the ring in Paris on September 9th, 1937, where a sold-out crowd watched him knockout Andre Regis. Shocking the audience and the sports world, Brown was carried off in triumph by supporters and when he returned to his hotel, kissed Cocteau for helping bring him back to life. Brown rounded out the triumphant year with another four matches, all ending in victory by KO.

As the victories, accolades, and money returned, Brown began to neglect his training again, and gradually shifted back to smoking and drinking. The following year, Brown was permitted his much-desired rematch with sworn enemy Sangchili, who was still the IBU champion. Brown began the match-clinching victories in early rounds, but by the tenth Sangchili was hitting much harder, and it looked like Brown was fading. Bloodied and wobbling, Brown appeared about to collapse when the final bell rang, which meant Sangchili had run out of time to land a KO, and the bout would be decided by the judges. As Roberts helped Brown onto a stretcher, the battered boxer was declared the winner and once again became IBU champion.

Cocteau relished in the fact that Brown had achieved redemption, but also saw the writing on the wall, and out of love and concern for Al, pleaded that the boxer retire. In an open letter to his lover he wrote, “You promised me to regain your title and I promised you to help yourself to the end in this amazing quest. It is done...take advantage of your triumph. Do not imitate the celebrities who cling. After the wonder of this revenge, give to the world the example of a man who leaves the room for young people...One last match; Angelmann. Be wise and leave the scene. This is my last advice.” Following 48 hours of deliberation, Brown conceded that Cocteau was right and that he would retire after one more fight. Brown KO’d Angelmann in 8 rounds and retired on a high note.

But the high note would not last. Brown returned to the nightlife after Cocteau arranged for him to perform at the Cirque Medrano. When the Medrano contract ran out, Brown found work with the traveling Cirque Amar, who also did not renew his contract. Meanwhile, Cocteau became a fading presence in Brown’s life, as the poet was in pursuit of his next lover, Jean Marais. Political history also proved unkind to the boxer. With the onset of WWII, Brown was advised he’d be better off in New York than staying behind in Europe. Reluctantly, Brown returned to the States in 1939, settled back in Harlem, and tried to find cabaret work like the kind in Paris, however, there was none to be had. Aimless, Brown returned to the gym and asked for a fight, abandoning retirement and achieving two knockout victories in a row.

Willing to return to the ring, Brown struggled with getting relicensed to box in the States, and without steady work either performing or boxing, he turned to drugs, this time seeking income via trafficking by pushing heroin in pubs and Central Park. By 1940, Brown had been arrested twice and in 1941 found himself in court, whereafter he was deported to Panama and banned from re-entry. There, Brown once again went looking for a fight. He worked with local promoters and hired new managers, racked up another three knockouts, and earned himself the Panamanian featherweight title. Meanwhile, he still struggled heavily with addiction, and now struggled to live openly gay, which was much easier to hide in New York or Paris than in the small and highly conservative Panama.

Brown once again stowed aboard a ship sailing to New York, feeling it was the best place for him to anonymously blend in. He began washing dishes and spending nights in Central Park and out of desperation, returned to the gym to try and fight, but given his history, trainers and boxing pros refused him. Instead, Brown settled and served as a sparring partner for up-and-comers at a gym in Harlem, where he gave pointers to young fighters and took a lot of beatings, earning a dollar a round. He continued in this debilitating role for almost two years, and combined with addiction, he experienced homelessness and frequent hospitalizations. In 1948, Jean Cocteau paid Brown a visit to the U.S. and was astonished by what he saw. Cocteau kissed Brown on both cheeks in the lobby of an upscale hotel, much to the shock of the neighboring white clientele, as segregation was still very much prominent in the States. In a final attempt to help his former lover, Cocteau reached out to his dear friend Edith Piaf and asked if her partner, Marcel Cerdan, a newly prominent fighter in the boxing world, could help take Brown under his wings. Cerdan, unfortunately, died in a plane crash a month later.

In 1950, Brown fainted on the corner of 42nd street and was found unconscious. As a result of being a homeless Black man, the police who arrived on the scene first took Brown down to the police station, unaware of the true circumstances. Brown was transferred to Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, where he clung to life for six more months before succumbing to tuberculosis on April 11th, 1951. At the age of 48, the great, barrier-breaking Alfonso Teófilo Brown died.

Brown’s body was first buried in Long Island City with a tombstone that simply read “Al Brown - 1902-1951.” A short time later, a Panamanian sports editor raised $750.00 to have Brown’s remains exhumed and shipped to Panama, where he was interred in what would be his final resting place in Panama City, with a tombstone that this time at least read, “ Alfonso Teófilo Brown, gloria nacional del boxeo.” At that point, Brown had become a national idol in Panama and Latin America, and magazines like Ring En Espanol continued to talk about his accomplishments for 60 years.

Brown’s final professional boxing record is debated but falls between an impressive total of 123-131 wins, 18-20 losses, 10-13 draws, and a whopping 55-59 knockouts which puts him in a very exclusive list of boxers who achieved 50 or more wins by KO in their careers. In 2002, Brown was named one of the 80 best fighters of the past 80 years by The Ring Magazine and was ranked #5 on BoxRec’s list of the greatest bantamweight boxers of all time. Brown has also since been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Finally, and perhaps most important to his legacy, Brown is recognized today as an LGBTQ pioneer, a Black man who had the guts to live out of the closet during a period in history when doing so had career-damaging consequences and in a sports industry that to date continues to be rife with unresolved homophobia and anti-Blackness.

As Jose Corpas, essentially Brown’s sole biographer, put it best:

“It wasn’t just the money that drove Brown. The feeling that consumed him when the bell rang had no price tag. When the bell rang he was chief, king, the boss and everyone watching knew it. For someone who was often told he should be ashamed of who he was, that feeling of superiority was addictive. The respect and awe his ring dominance earned him spilled out into the cabarets and streets where Brown was often the richest, most famous, and toughest man in the room. As a result, he was the best dancer, best singer, and best looking man in the room too. When he couldn’t box, he was a poor, skinny, gay drunk. Walking away from boxing meant walking away from being special.”

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Arnaud, Claude. Jean Cocteau: A Life. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2016.

Berlin, Adam. “Panama Al Brown, Boxing’s First Latino Champion.” WBA Boxing. (2016, September 13).

https://www.wbaboxing.com/boxing-news/panama-al-brown-boxings-first-latino-champion#.YYancjZKiWA

Corpas, Jose. Black Ink. Iowa City, KO Publications, 2016.

Krebs, Joey. “Black, Gay and Undocumented: The Story of Boxing’s First Latino Champion.” El Tecolote. (2021, March 12).

McLachlan, Kyle. “The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No. 8: Panama Al Brown.” The Fight Site. (2019, November 4).

https://www.thefight-site.com/home/the-all-time-great-bantamweights-no-9-panama-al-brown

Meneses, Álvaro Sarmiento. “Al Brown: Strikes Again.” Revista Panorama. (2016).

https://www.revistapanorama.com/en/al-brown-strikes-again/

Stovall, Tyler. Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light. Santa Cruz, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.