“In the life of a revolutionary, prison is an occupational hazard.”

– Luis González de Alba

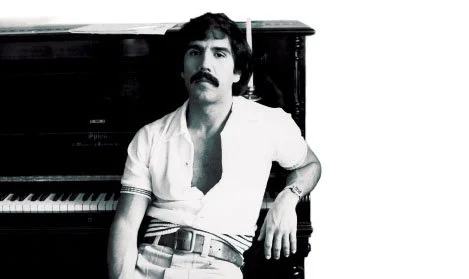

A provocative dissident, writer, psychologist, and early advocate for sexual diversity, Luis González de Alba was among the most fearless and multifaceted public intellectuals in modern Mexican history. Though less internationally known than many of his contemporaries, he helped bridge the worlds of political resistance, literary innovation, and queer visibility at a time when being openly gay in his country remained both dangerous and transgressive. His life–marked by dogged defiance and constant reinvention–carried him from the barricades of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre to the editorial pages of Mexico’s leading newspapers and from behind prison walls to the founding of his country's first gay liberation movement. Through his writing, intellect, and unrelenting activism, González de Alba helped redefine what it meant to live and write openly as both a radical activist and a gay man in post-Tlatelolco Mexico.

Luis González de Alba was born on March 6th, 1944, in Charcas, San Luis Potosí. He was the eldest son of Luis González Iracheta and Esther de Alba, who were both originally from Jalisco and who moved their family back to the region when Luis was ten years old. In his late teens, Luis moved to Mexico City to study psychology at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico), where he quickly became involved in the Mexican Student Movement of 1968 and a leading voice of the National Strike Council. During this time, Luis was also involved in one of his first openly gay relationships with a veterinarian named José Augusto “Pepe” Delgado, whom he would later consider to be one of the loves of his life.

On the night of October 2nd, 1968 González de Alba’s life would take a pivotal turn when he was arrested during the Tlatelolco Massacre, a watershed event in Mexican history. Dozens of Mexican students fighting for social justice were brutally murdered by order of the country’s repressive government, while many more–including Luis–were arrested and tortured. González de Alba was then imprisoned for two and a half years at the notorious Lecumberri prison, nicknamed The Black Palace. While detained there, he wrote Los días y los años (The Days and the Years), a groundbreaking memoir that challenged both government and opposition narratives and which to date remains an essential eyewitness account of the events of the October 2nd Massacre.

Upon his release, González de Alba lived for a time in self-imposed exile, temporarily residing in various locations across Latin America before returning to Mexico and gradually becoming one of the country’s most outspoken advocates for LGBTQ+ rights. Indeed, González de Alba lived his life as an openly gay public figure at a time when few in Mexico were. In 1973, he met an actor named Ernesto Bañuelos, with whom he began a long-term relationship that would last for over a decade.

Also at this time, Luis became a founding member of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (Homosexual Liberation Front), his country’s first public gay protest organization. This group would eventually count notable activists like Braulio Peralta, José María Covarruvias, and Teresa Chaustelli among its ranks. Despite his prior imprisonment, González de Alba’s activism throughout the ‘70s remained both unapologetic and often risky: he endured raids, used aliases to evade harassment, and frequently channeled his advocacy through literature, journalism, and social engagement. With collaborators Nancy Cárdenas and Carlos Monsiváis, he co-authored Mexico’s first pro-homosexuality manifesto, published in the magazine Siempre! in 1975. The manifesto, entitled “Against the practice of the citizen as police booty,” highlighted the criminalization of homosexuality and demanded a stop to police violence against the LGBTQ+ community. In it, the authors wrote: “It is possible to accuse a person of rape or corruption, but not of being homosexual, just as one cannot accuse them of being blond, tall, left-handed, or handsome–conditions perhaps less frequent than being homosexual.”

Three years later, on July 26th, 1978, González de Alba also played a pivotal role in organizing a group of openly LGBTQ+ people to march in the streets of Mexico City for the first time, demanding social recognition and respect from Mexican society and the government. This marked a turning point in queer Mexican history and is considered to be the beginning of Mexico City’s now annual Pride March.

In the 1980s, alongside his partner Ernesto Bañuelos, González de Alba opened La Tienda del Vaquero (The Cowboy Shop) and La Cantina del Vaquero (The Cowboy Cantina), two pioneering commercial spaces in Mexico City that explicitly catered to gay men. These venues were inspired by the leather bars Luis had experienced in the U.S. and became crucial social centers for homosexual, bisexual and curious men–selling literature, screening pornography, and offering safe spaces for same-sex encounters. He also helped launch El Taller, one of the first openly gay bars in Mexico to host HIV/AIDS education programming. The bar, located in a basement in Mexico City’s Zona Rosa district, served as the venue for his "Tuesdays at El Taller" project, which included lectures, group discussions and other activities aimed at fighting back against the HIV/AIDS pandemic. These meetings ultimately led to the establishment of the Fundación Mexicana de Lucha contra el SIDA (Mexican Foundation for the Fight Against AIDS) in 1987. Tragically, that same year, Luis lost his beloved Bañuelos to AIDS. Spreading salt on the wound, Bañuelos’ family excluded Luis from being present during Bañuelos’ final days. Shaken by this appalling event, González de Alba was propelled into becoming an early advocate for the legal recognition of same-sex partnerships.

All the while, he remained a prolific author, publishing both fiction and essays that explored sexuality, science, and memory. Among others, his notable works include Y sigo siendo sola (1979), El vino de los bravos (1981), Las compañías difíciles (1984), and Agápi mu (1993), the latter of which was adapted into a film in 2004. He also worked as a science columnist, most notably for La Jornada, a paper he helped found, and later for Milenio. Across his varied writings, he was an intellectual provocateur, unafraid to publicly challenge close associates like Elena Poniatowska or Carlos Monsiváis when historical or ideological disagreements arose. His 1997 essay, in particular, entitled "Para limpiar la memoria," led to a lawsuit and a legal victory that forced revisions to Poniatowska’s book La noche de Tlatelolco, further cementing his role as a participant, critic, and preservationist of the 1968 massacre’s legacy. That same year, he received the National Journalism Prize for his work in helping to popularize science writing in Mexico.

Later in life, González de Alba settled in Guadalajara, himself living with HIV and dealing with chronic vertigo. Despite these personal setbacks, he continued to speak out, write and publish, penning notable works like No hubo barco para mí (2013) and the posthumously published Mi último tequila and Tlatelolco: Aquella tarde. On October 2nd, 2016–48 years to the day after the Tlatelolco Massacre–González de Alba died by suicide at the age of 72. With this consciously-orchestrated death, he left behind explicit instructions for his cremation as well as for the stewardship of his extensive archive, which is now split between ITESO (Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education) in Guadalajara and a private collection overseen by his nephew Adrián Cortéz.

Upon learning of his death, Marcelino Perelló, a longtime intellectual adversary of González de Alba, remarked that Luis “was a courageous man, essentially honest and upright, despite the poor relationship we had, which certainly changed in recent times, with some attempts at reconciliation…He wasn't like others who took advantage of the public attention that '68 gave us. He didn't use it to climb to political or public positions, but instead chose a nobler path: literature and the popularization of science.” Perelló also commented on González de Alba’s literary legacy: “There is a great freshness in his writing, regardless of the debate his content may provoke. He was a breath of fresh air in a somewhat bleak landscape, when many of the leaders of that movement were mired in crude and opportunistic activities.”

Though he is now considered one of the most prominent gay intellectuals in Mexican history, it is worth noting that at numerous times in his life González de Alba controversially rejected the notion that there ever existed a defined "lesbian-gay community,” arguing instead that "there are homosexuals of all kinds." At times, he would also distance himself from the label of "defender of homosexual rights," stating: "I have never wanted to champion the cause of homosexual human rights or anything like that. I don't belong to any group, nor do I have good relations with that world. What's more, everyone there detests me for my different way of understanding homosexuality."

Taking these comments and others like these into account, it is easy to glean that Luis González de Alba was both a complex and sometimes polarizing figure. Nevertheless, his contributions to Mexican public life–particularly in the realms of LGBTQ+ rights, student protest, and cultural criticism–are undeniable. His legacy, however, resists easy categorization; he was an activist and a skeptic of activism, a revolutionary who questioned revolutions, and a gay man who defied the confines of gay identity. Yet through his writing, organizing, and unflinching intellect, he carved a permanent space for queer presence within Mexico’s cultural and political imagination. His voice, which could alternate with ease from being tender to polemical to rigorously self-critical, remains a testament to the courage required to live authentically in a country still learning to embrace its own diversity. Whether he is remembered as a rebellious student during a politically defining moment, as a chronicler of injustice, or as a pioneering queer thinker, González de Alba stands as a reminder that the most radical acts often stem from a persistent refusal to conform. His body of work endures not only in his books and archives but in the safer, more visible world he helped carve out in Mexico for the queer generations that followed.

When trying to succinctly encapsulate Luis González de Alba’s life, writer Hector Osorio Lugo perhaps said it best: “[He was] an exceptional figure…often going against the grain, even going against the grain of himself, extremely perceptive, sarcastic to the point of exposing the object of his criticism, rabidly cultured, erudite, a music lover, a composer, a polyglot, a great writer, a science communicator, a co-founder of political parties, a pioneering standard-bearer of sexual diversity…and much more.”

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Bernal, D. B. (2018). Not Even all the Bullets Can Beat Us: The Literature on ’68. Voices of Mexico, 106. https://www.revistascisan.unam.mx/voices/pdfs/10626.pdf

Castellanos, J. C. (2016, October 24). “El odio de gonzález de alba me Persiguió Toda la vida”: Poniatowska. Aristegui Noticias. https://aristeguinoticias.com/2410/kiosko/el-odio-de-gonzalez-de-alba-me-persiguio-toda-la-vida-poniatowska/

Espinosa, C. A. (2016, October 4). La noche de Tlatelolco: El pecado de Elena Poniatowska. InfoCajeme.com. https://www.infocajeme.com/cultura/2016/10/cuando-luis-gonzalez-de-alba-desmitifico-a-elena-poniatowska/

González de Alba, L. (2010, October 1). My fight with the left. Nexos. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=13951

Heroles, F. R. (2016, November 24). Adiós a Luis González de Alba. Este País. https://estepais.com/impreso/adios-a-luis-gonzalez-de-alba/

Lugo, H. O. (2016, October 4). El día que Luis González de Alba obligó a Elena Poniatowska a corregir su obra cumbre. Yahoo! https://es-us.noticias.yahoo.com/el-d%C3%ADa-que-luis-gonz%C3%A1lez-1529940747296822.html

Muñoz, M. (2011). La literatura mexicana de transgresión sexual. Amerika, 4. https://doi.org/10.4000/amerika.1921

Romero, L. M. (2024, October 2). Rostros LGBT+: Luis González de Alba. Escándala. https://escandala.com/rostros-lgbt-luis-gonzalez-de-alba/

Sánchez H, A., & González de Alba , L. (2016, October 4). ¡González de Alba, despedido del diario de la izquierda!. Revista Replicante. https://revistareplicante.com/gonzalez-de-alba-despedido-del-diario-de-la-izquierda/

Talavera, J. C. (2016, October 3). Luis González de Alba, no se olvidará. Excélsior. https://www.excelsior.com.mx/expresiones/2016/10/03/1120211

Ulises, E. (2023, April 17). Luis González de Alba, El Líder Gay del 68. Homosensual. https://www.homosensual.com/cultura/historia/luis-gonzalez-de-alba-el-lider-gay-del-68/

Zacarias, M. (2023, June 5). Potosino Luis González de Alba, fundó Defensa de Comunidad LGBT+. Quadratin San Luis Potosí. https://sanluispotosi.quadratin.com.mx/san-luis-potosi/potosino-luis-gonzalez-de-alba-fundo-defensa-de-comunidad-lgbt/

Zermeño, A. (2021, March 13). Luis González de Alba, El Potosino pionero en la Defensa de los Derechos LGBT. La Orquesta. https://laorquesta.mx/luis-gonzalez-de-alba-el-potosino-pionero-en-la-defensa-de-los-derechos-lgbt/

Zerón-Medina Laris, T. (2013, December 1). Luis González de Alba, in profile. Nexos. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=1560