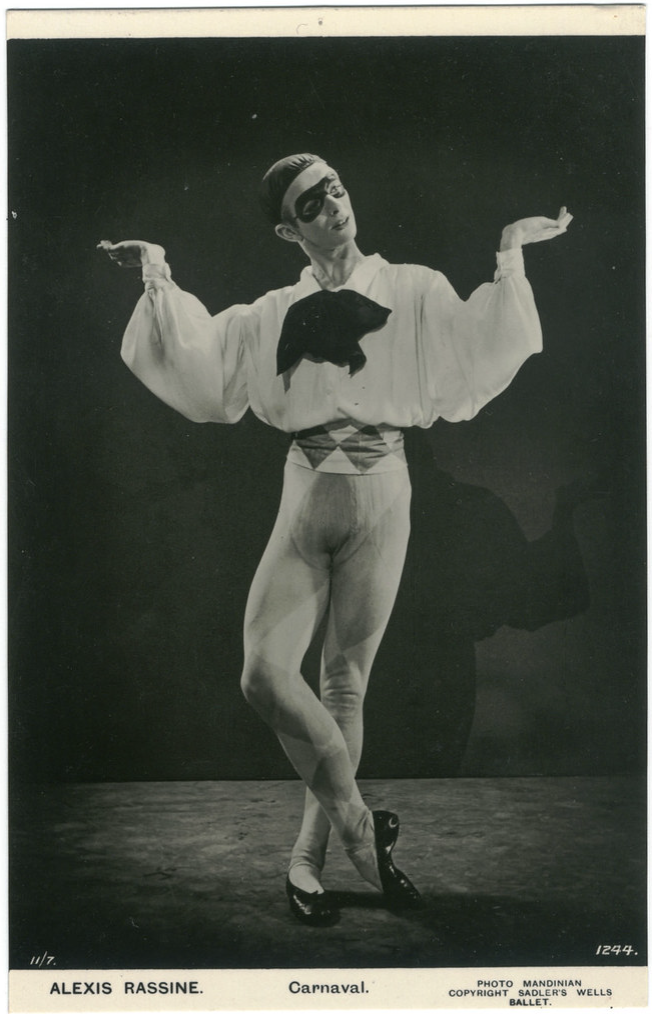

Black and white photo of Alexis Rassine in Carnaval. Photo by Edward Mandinian, Copyright Sadler's Wells Ballet

“Nevertheless, I had a big thrill watching the youthful Alexis Rassine dancing the male role. He is truly musical, and while his technique appeared to be faultless, it took second place to his phraseology of steps, which would have delighted the romantic Chopin himself.”

– Kay Ambrose

Though his name may not be widely known today, Alexis Rassine remains a vital figure in the history of British ballet, particularly during the wartime and immediate postwar years of World War II. Lithuanian by birth, South African by nationality, and European by training, Rassine became a luminous presence across continents, stages, and boundaries of identity and nation, particularly during his time with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet during the 1940s and early 1950s. While at Sadler’s, he performed in countless lead roles alongside ballet legends like Margot Fonteyn, Robert Helpmann, and Nadia Nerina, at a watershed time when the Second World War depleted the ranks of male dancers. During this era, Rassine stepped up to the stage with elegance, discipline, and lyrical charisma—and his contributions to dance helped sustain British ballet during a volatile period of global upheaval.

Rassine was born Alec Raysman (originally Reisman) in 1919 to Jewish Russian parents in Kaunas, Lithuania. The youngest of three brothers, Rassine's early life was already defined by movement–in his earliest years his family frequently drifted between Saint Petersburg and Lithuania due to the unstable political climate, and by the time he was ten years old the family left the country altogether, settling in Cape Town, South Africa. Though he initially spoke Russian with his family, Rassine subsequently learned to speak English and eventually inherited a South African passport.

As a young teenager, Rassine began dancing under the tutelage of Helen Webb and Maude Lloyd. His talent quickly became evident, and at eighteen he left South Africa for Paris to study with the famed Russian émigré teachers Olga Preobrajenska and Alexandre Volinine. While studying, he made his professional debut there at the cabaret Bal Tabarin, a renowned Parisian nightclub. After failing to secure a place at the Paris Opera Ballet, however, Rassine pressed on to London, arriving there in 1939 nearly penniless. Through a combination of his own sheer talent and the fortuitous scarcity of male dancers, he was able to find generous teachers, including Stanislas Idzikowski, Igor Schwezoff, and Vera Volkova who recognized his promise and offered him free tuition. After a brief stint with Ballet Rambert, he then joined the touring ensemble called the Trois Arts Ballet, where he gained both vital stage experience and was able to learn key fragments of the classical repertoire.

That experience, however, was cut short by the German invasion of Poland in 1939. But towards the end of 1940, a group of Polish refugees formed the Anglo-Polish Ballet and invited Rassine to join. He soon became its leading classical soloist, performing in pieces like Michel Fokine's Les Sylphides and Cracow Wedding. Rassine’s biggest breakthrough came when Ninette de Valois of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet—impressed by his grace and presence—offered him a contract in 1942. For the next thirteen years, Rassine danced principal roles in canonical ballets like The Sleeping Beauty, Giselle, and Coppélia, while also creating roles in new works by Frederick Ashton, Robert Helpmann, and de Valois herself. He was most celebrated for performing the Bluebird in The Sleeping Beauty and as the Spectre de la Rose in the ballet of the same name—roles that demanded lyricism and finesse more than bravura. Other notable roles favorited by audiences included the Snob in Léonide Massine's La Boutique Fantasque, the Harlequin in Michel Fokine's Carnaval, and the Vestris in de Valois's The Prospect before Us. Rassine’s supple, birdlike line and gentle charisma also made him a compelling dance partner to many celebrated ballerinas including Margot Fonteyn, Nadia Nerina, Pamela May, and Violetta Elvin.

Back in South Africa, Rassine was seen as both a patriot and a pioneer. He returned to the country for several high-profile tours alongside Nerina in both 1952 and 1955, performing for whites-only audiences under apartheid but nonetheless committed to enriching the nation’s cultural life. His performances, though circumscribed by the racist policies of the state, helped bring world-class ballet to the region. Yet he, like Nerina, ultimately did not return to live in the country, choosing instead the more expansive—and socially accepting—creative sphere of postwar Europe.

Even at his peak, Rassine remained somewhat distant and aloof. He was noted for being rather flamboyant, and for concealing deeper insecurities regarding his homosexuality. Several of his fellow dancers nicknamed him the ‘Cockadoodle,’ due to his beak-like nose and fairly high-pitched voice that combined a mid-European accent with South African overtones. Additionally, Rassine never felt quite secure performing in the highest ranks of the Wells Ballet, especially once other male dancers like John Hart, Harold Turner, and Michael Somes—now also noble war veterans—returned to reclaim the stage.

Nevertheless, Rassine during the war was a considerable and vital asset to Sadler’s Wells Ballet, performing alongside Robert Helpmann in nearly all of the major male roles. He and Helpmann’s styles and personalities were different enough that the two were able to work alongside one another without much competition or jealousy. But by 1952, the new wave of male dancers had taken over. Their youth and physicality pushed Rassine and Helpmann out of leading roles, and Rassine often found himself relegated to second or third-tier casts. Helpmann soon left the ballet to pursue a successful acting and film career, and he eventually became the principal choreographer and artistic director of the Australian Ballet. Rassine, however, was not so fortunate. By the mid-1950s, Rassine’s roles continued to diminish as new stars emerged, and it was clear that his time with Wells was over. He left Sadler’s in 1955 in search of new opportunities, and danced for a time with Walter Gore’s London Ballet and at various international galas.

Soon thereafter, Rassine faded from public view. A cosmetic surgery to reduce his aquiline nose—perhaps reflecting a desire to assimilate or soften his image—coincided with a growing personal reticence. Some critics went so far as to note that the alteration of Rassine’s nose diminished–to an extent–his personality. In any case, Rassine retreated from the spotlight, teaching private pupils occasionally in London but otherwise living quietly in the Sussex countryside.

Beyond the stage, though, Rassine also lived a deeply private life shaped by a long-term romantic and intellectual partnership with the poet and publisher John Lehmann. Their companionship, which began around 1940 and lasted until Lehmann’s death in 1987, was marked by mutual devotion. While Rassine never publicly commented on his sexuality, their relationship—quiet but enduring—has been preserved in archives, private papers, and recollections by literary contemporaries such as Christopher Isherwood. In a time when few could live openly, Rassine’s domestic life was one of quiet queerness, anchored by chosen family and artistic affinity. After John’s passing, Rassine spent his final years remotely, living a solitary life in the cottage left to him by Lehmann.

Rassine himself ultimately passed away on July 25th, 1992—just one day before his 73rd birthday. While he never received the full recognition that his wartime contributions deserved, his impact endures in the legacy of British ballet and in the memories of those who danced beside him. As the “least English” of the Sadler’s Wells company, he brought a distinct grace and cosmopolitan lyricism to the stage, helping to carry the artform through an era of scarcity and transformation. Meanwhile, quietly but unmistakably, Rassine’s long-term partnership with John Lehmann marks him as an important queer presence in ballet history—a reminder of the hidden yet enduring influence of LGBTQ+ figures in the arts. Today, Rassine’s story reminds us of how dance and the dancers who give it life can transcend borders, sexualities, conflicts, and time.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Ambrose, K. (1941). Balletomane’s Sketch-Book. A&C Black.

Chujoy, A., & Manchester, P. W. (1967). The Dance Encyclopedia: Revised and Enlarged Edition. Simon and Schuster.

Clarke, M. (1955). The Sadler’s Wells Ballet: A History and an Appreciation. A&C Black Limited.

Clarke, M., & Vaughan, D. (1977). The Encyclopedia of Dance & Ballet. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Gregory, J. (1992, August 3). Obituary: Alexis Rassine. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-alexis-rassine-1537962.html

Grut, M. (1981). The History of Ballet in South Africa. Human & Rousseau.

Rolle, E. (2015, July 26). Alexis Rassine & John Lehmann. LiveJournal. https://elisa-rolle.livejournal.com/2218362.html

Salter, E. (1978). Helpmann: The Authorised Biography. Angus and Robertson.

Walker, K. S. (1987). Ninette De Valois: Idealist Without Illusions. Hamish Hamilton.