“We are trying to create a Negro dance idiom independent of the classic ballet…The ballet is not African, but Negro. There is a great difference which people in Europe fail to realise. Negroes are the children of Africa scattered all over the world. They adopt the culture of the respective country [where] they happen to reside–hence the term Afro-American...”

– Berto Pasuka

Arriving in Britain on the eve of the Second World War, Berto Pasuka stands as one of the most innovative and overlooked figures in twentieth-century performance. A queer artist from Jamaica, he entered a cultural landscape that left little room for Black dancers or Black creative leadership, yet he refused to be restricted by the narrow expectations and offerings of his time. Instead, he insisted that Black movement, Black stories, and Black aesthetics belonged on major stages, and pushed to create a dance language rooted in the rhythms, histories, and expressive traditions of the African diaspora. His vision not only challenged the limits of European ballet but also reshaped what dance in postwar Britain could be, ultimately laying the groundwork for a new chapter in Black performance.

Born Wilbert Passerley in Jamaica in 1911, Berto Pasuka grew up in a family that hoped he would pursue a respectable profession–like dentistry–which could earn him a steady income. Instead, he chose a path that, in their eyes, seemed far less secure: he wanted to dance for a living. He soon began studying classical ballet in Kingston, where he learned the vocabulary and posture of European technique. Concurrently, he started to look beyond it for movements that resonated more with his own experience as a Black man from the Caribbean. According to one story that recurs in accounts of his early life, Pasuka described watching the descendants of runaway slaves dancing to the beat of drums in Jamaica. The power and spontaneity of their movements left a lasting impression on him and would eventually inform his efforts to create a new dance idiom that drew from both classical ballet and Afro-Caribbean tradition.

Before leaving Jamaica, Pasuka performed in local shows and for tourists, already experimenting with ways he could present Caribbean music and movement to wider audiences. Fairly quickly, he desired a larger stage, and in 1939, he traveled to Britain, joining a small but growing community of Caribbean migrants who had immigrated before the more famous 1948 Windrush generation’s arrival. Later writers suggest that part of Pasuka’s motivation to leave Jamaica at this time was also his desire to escape the prejudice he faced back at home as a queer Black man.

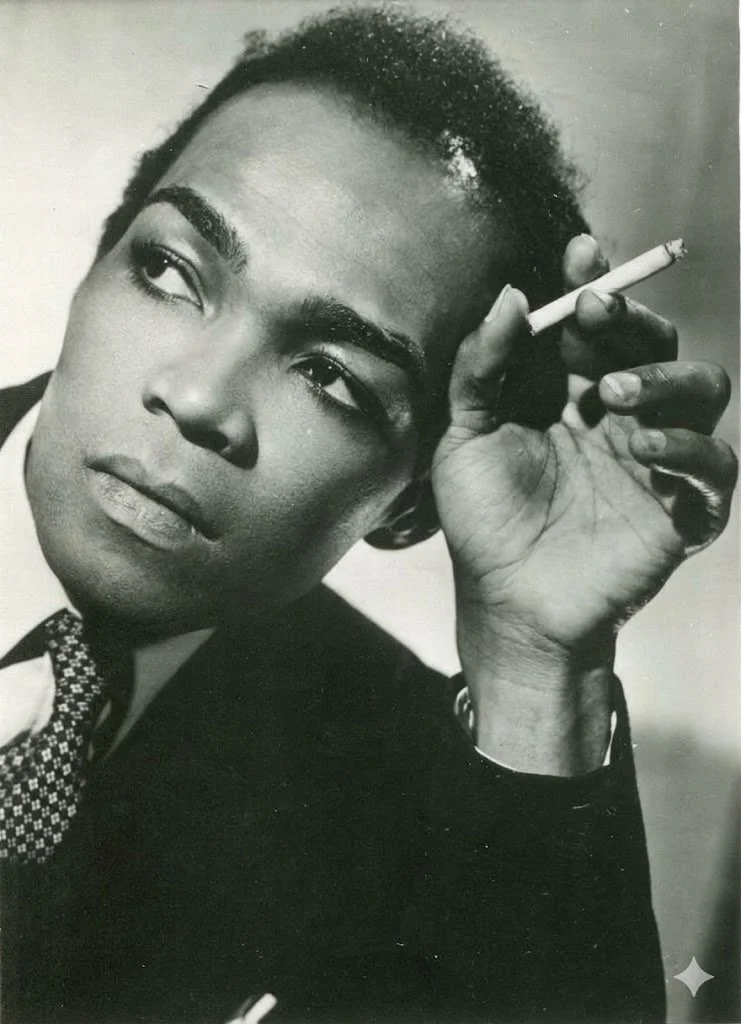

After landing in London, Pasuka continued his training at academies such as the Astafieva Dance School, where many of the city’s classical dancers had trained. The outbreak of the Second World War, however, quickly narrowed opportunities, but he survived by dancing in cabaret shows in West End nightclubs and working as a model for various sculptors, painters, and photographers. His strong, expressive presence attracted the attention of the Welsh photographer Angus McBean in particular, himself a notable queer figure in British cultural life. McBean’s stylized portraits of Pasuka–now held in collections such as the National Portrait Gallery and Harvard Theatre Collection–are among the few surviving images of him, and collectively help situate Pasuka within Britain’s mid-century queer artistic network.

During and just after the war, Pasuka’s film work also helped set the stage for what would become his most important project. In 1946, he was hired to dance in and recruit performers for the film Men of Two Worlds, which mixed colonial fantasy with images of African “witch doctors” for British audiences. Drawing on the dancers and musicians he met there, and joining forces with fellow Jamaican dancer and artist Richie (Ritchie) Riley, Pasuka began to work on a long-held vision of his: a Black-led ballet company that would present what he called “Negro ballet” on its own terms.

The landmark Les Ballets Nègres (often also rendered Ballets Negres) officially debuted in April 1946 at the Twentieth Century Theatre in Westbourne Grove, London. It is widely recognized as both Britain’s and Europe’s first Black ballet company. Under Pasuka’s artistic direction, and with Riley as his closest collaborator, the troupe assembled dancers and musicians from a multitude of countries, including Jamaica, Trinidad, Ghana, Nigeria, Guyana, Germany and Britain. Nigerian drummers like Bobby Benson and Ambrose Campbell were also brought in to provide the percussive backbone for many of the troupe's works, emphasizing the company’s diasporic reach.

The company’s subsequent repertoire drew on Afro-Caribbean folk tales, religious rituals, and everyday Black social life, translated into a staged form that neither replicated European ballet nor simply reproduced folk dances. In his description of the company’s aims, Riley wrote that “Negro ballet is something vital in choreographic art…an expression of human emotion in dance form, the complete antithesis of Russian ballet, with its stereotyped entrechats and pointe work.” Pasuka’s choreography fused “basic (not tribal) steps” with deliberately “spontaneous moments,” insisting that this mixture constituted its own technique. For him, the goal was to create a modern Negro dance expression distinct from classical ballet, Indian dance, or European modernism–one rooted in the experience of Black people of the African diaspora, “children of Africa scattered all over the world” who had adapted to and adopted the cultures of the places where they lived.

Les Ballets Nègres’ early seasons were a revelation to both audiences and critics alike. The troupe’s very first program included works such as De Prophet, They Came, and Market Day, pieces that were later broadcast on BBC television. The company soon moved to larger venues, including the Gate Theatre and the Playhouse, and began touring widely across Britain and continental Europe to enthusiastic houses. At their peak, Les Ballets Nègres employed around twenty-one dancers, eighteen of whom were Black–an unprecedented sight on British ballet stages in the 1940s.

After this initial wave of excitement waned, critical responses could then be admiring and condescending in equal measure, with some reviewers praising the company’s “fervent integrity” while questioning its “art.” In a now-famous exchange of letters with critic Annabel Farjeon in 1952, Pasuka defended Les Ballets Nègres against such judgments. He rejected the idea that the company’s improvisatory quality was a sign of amateurism, arguing instead that spontaneity was integral to their choreographic language and needed to be judged by its own standards, not by those of Russian or British ballet. “Would you say ice-cream is no good because it is not cheese?” he wrote, using caustic humour to reinforce his most serious point, that Black dance in Britain should not have to justify itself by mimicking white European forms.

Despite its artistic success and sold-out tours, however, Les Ballets Nègres still struggled financially. In a post-war arts landscape where public subsidy and private patronage were increasingly important, the company was repeatedly denied the support that white-led institutions were receiving at the time–a disparity that many later commentators have linked directly to racism. On occasions, fervent supporters such as Cambridge law fellow Bryan Earle “Rufus” King helped to cover wages, but by the early 1950s, the company could no longer survive on box-office income alone. It disbanded around 1952–53, leaving behind only a handful of programs, reviews, and scattered archival traces.

When his dream company closed, Pasuka’s life followed an increasingly precarious but still intensely creative path. He continued to dance, including a final major stage appearance at the Royal Court Theatre in 1959 in Sean O’Casey’s Cock-a-Doodle Dandy, where he performed as the titular cockerel. He also deepened his work as a model and visual artist. Based for a time in Paris, he trained as a painter and exhibited with the Société des Artistes Indépendants at the Grand Palais in 1959. The following year, he mounted a solo exhibition of twenty-eight paintings in London, expanding his exploration of Black diasporic life, spirituality, and history into another medium.

Throughout this productive but haphazard period, Pasuka moved within overlapping Black, Caribbean, and queer circles in London and Paris. Accounts suggesting that he had left Jamaica in part to escape homophobic prejudice aligned with later rumours which held that he may have died following an altercation with a male lover. The details of his actual personal relationships, however, remain fragmentary. Likely, these were shaped by cautious silence and a “politics of delicacy” similar to those that led his colleague Richie Riley to deflect questions about his own sexuality in a later queer oral history interview. While his personal life details remain murky, what is clear is that Pasuka’s work–onstage, on film, in front of McBean’s camera, and on canvas–emerged from a life lived at the intersection of Blackness, migration, and queerness in mid-twentieth-century Europe.

Tragically, Pasuka died prematurely in London in 1963, after being found ill in his Paris apartment and transferred to a hospital in Wimbledon. For decades after his untimely passing, both he and Les Ballets Nègres were largely absent from standard narratives of British dance history, their pioneering role often reduced to a footnote, if mentioned at all. Despite this erasure, their influence persisted in the bodies and careers of the dancers they trained and inspired, and in the wider development of dance of the African diaspora in Britain. Artists such as Elroy Josephs and later Black British companies drew, directly or indirectly, on the model that Pasuka and Riley had proposed: work that fused African, Caribbean, and European techniques; highlighted Black stories and spiritual traditions; and insisted that Black dancers belonged at the center of the stage.

In more recent years, historians, curators, and artists have begun to recover Pasuka’s story and reposition him as a foundational figure in Black British and queer performance history. The National Portrait Gallery, for example, has exhibited McBean’s iconic portraits of him. Meanwhile, tributes at the Royal Festival Hall and exhibitions like Into the Light: Pioneers of Black British Ballet have spotlighted Les Ballets Nègres as an essential ancestor to contemporary Black dance in the UK. Scholars have also undertaken more dedicated research into Pasuka’s life and work, situating him within a broader history of Caribbean migration, colonialism, and queer Black creativity.

Remembering Berto Pasuka today means more than just honoring a “first.” It means recognizing how a Black queer Jamaican artist, working amid the constraints of racism, homophobia, and post-war austerity, carved out space for new forms of Black movement and representation in Britain and Europe. His insistence that Les Ballets Nègres be seen on its own terms–as a distinct Negro dance idiom rather than an imitation of European ballet–remains a powerful example of challenging Eurocentric definitions of art. His legacy also lives on in every Black dancer who claims the stage as a place where diasporic histories, spiritualities, and desires can be fully expressed, and in every attempt to write queer Black artists back into the forefront of cultural history rather than leaving them in its margins.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Barnes, T. (2017). Presenting Berto Pasuka. In British Dance: Black Routes (pp. 15–34). Essay, Routledge: Taylor & Francis.

Bayly, M. J. (2022, July 12). “Creative Outsider, Determined Innovator”: Remembering Berto Pasuka. “Creative Outsider, Determined Innovator”: Remembering Berto Pasuka. https://thewildreed.blogspot.com/2022/07/creative-outsider-determined-innovator.html

Bourne, S. (2025). Trailblazers of Black British Theatre: From Ira Aldridge to Cleo Laine. The History Press.

Bunyan, M. (2016, December 5). Berto Pasukaart Blart _ Art and Cultural Memory Archive. Art Blart _ art and cultural memory archive. https://artblart.com/tag/berto-pasuka/

Jones, J. (2024, June 11). Britain’s Queer Trailblazers: Berto Pasuka. Spectrum Outfitters. https://www.spectrumoutfitters.us/blogs/spectrum-spotlight/britain-s-queer-trailblazers-berto-pasuka

Mapping Dance of the African Diaspora. (n.d.). https://www.onedanceuk.org/media/cnwilexk/hotfoot-mapping-dance-of-the-african-diaspora.pdf

Mayes, S., & Whitfield, S. K. (2021). An Inconvenient Black History of British Musical Theatre: 1900-1950. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Rolle, E. (n.d.). Queer Places. Queerplaces - Berto Pasuka. http://www.elisarolle.com/queerplaces/a-b-ce/Berto%20Pasuka.html

Tuliptuitt. (2018, March 19). Tulip Tuitt. Tumblr. https://tuliptuitt.com/post/172015907850/an-exchange-of-letters-between-berto-pasuka-of

Watson, K. (1999, August 4). They were Britain’s First Black Dance Company. How Come No One’s Ever Heard of Them? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/1999/aug/05/artsfeatures1